A Journey

72 drawings by Si Lewen

with an introductory essay by Thomas Yoseloff

Philadelphia: The Art Alliance Press

London and Toronto: Associated University Presses

Copyright 1980 by Si Lewen

to Issac

Brother and travel companion

Si Lewen the man and his art

Introductory Essay by Thomas Yoseloff

When Si Lewen completed his first book of drawings, The Parade, in 1950, Albert Einstein wrote:

I find your work, The Parade very impressive from a purely artistic standpoint. Furthermore, I find it a real merit to counteract the tendencies toward war through the medium of art. Nothing can equal the psychological effect of real art-neither factual description nor intellectual discussion. It had often been said that art should not be used to serve any political or otherwise practical goals. But I could never agree with this point of view. It is true that it is utterly wrong and disgusting if some direction of thought and expression is forced upon the artist from outside. But strong emotional tendencies of the artist himself have often given birth to truly great works of art. One has only to think of Gulliver's Travels and Daumier's immortal drawings directed against the corruption in French politics of his time. Our time needs you and your work.

The Parade and its sequel, A Journey, spring from Lewen's past and emotional experiences. Si Lewen was born as the First World War was coming to an end, in 1918, in Lublin, Poland. Soon after, his parents fled with him to Berlin. In Switzerland, at the age of five, he decided to become a painter. Returning to Berlin, he received his first art lessons from Max Adron, a student of Paul Klee and the Bauhaus, and from Klaus Richter of the Berlin Academy. The political and cultural ferment of the Weimar Republic, and especially German Expressionism and the work of Kaethe Kollwitz, George Grosz, and Frans Masereel, added their influence.

In 1933, when Hitler came to power, young Lewen, then 14, fled to France. Here, he was fascinated by the modern French school, especially Cubism. Two years later he came to New York and continued his studies at the National Academy of Design. When the United States entered the Second World War, he joined the American Army and took part in the European campaigns from Normandy to Germany.

Back in New York after the war, he resumed his art studies and began work on his long series of continuously related drawings and paintings. The publication of The Parade in 1957 was the culmination of this phase of his work. In 1968, Lewen and his wife, Rennie, left New York City and settled in New Paltz, New York, where he has been working on the "Millipede"-a multimedia multiptych project of "continuous progression, procession and transformation." Already 1,000 feet long and still growing, it appears to Lewen to have no end in sight.

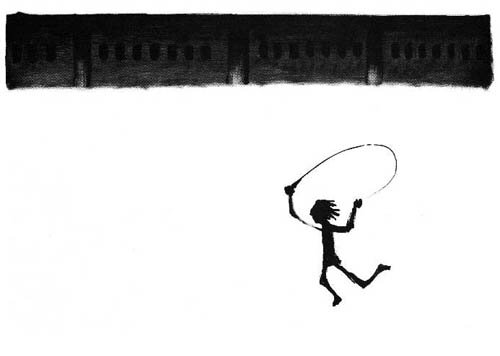

Si Lewen's work reflects a world of step-by-step progression of often tragic events and images. For him everything is but a step, a transition to the next stage. All of his work is a part of a procession, a migration, an Odyssey. In A Journey the "visitor" travels through the nightmare of the concentration camp, where the camp serves as the ultimate expression of the nation state.

Einstein found Lewen's work "impressive." Other distinguished critics have expressed their own reactions on seeing his work. August L. Freundlich wrote in 1962:

The work of Si Lewen is the work of a forceful giant with the sensitive conscience of the artist ...

Lewen's paintings are unusual in these days of abstract and wildly expressive art. He combines emphasis on precise design with an often scathing comment on the events in our lives. He is both artist and child of our century.

Lewen's artistic world shows the grimness and horror which exist in war and its aftermath, in the slums of the city, and in the changes which man has made detrimentally to his environment.

Meyer Levin, in writing about The Parade, said it was "so powerful that when I first looked through it I felt I could not write about it." It was, he said, "created with a fury that can only be compared to Goya's in the 'Horrors of War'."

The Parade and A Journey may be unique. Lewen acknowledges, however, that they were inspired and influenced by the "novels without words," the books of woodcuts by Frans Masereel, published in the 1920s. Lewen has written of his own motives in creating A Journey:

Of the "plot" and the symbolism in the work, he has written:

A Journey graphically describes, by means of its 72 drawings, the journey of a man. He enters a forest. The forest grows darker. Deep in the forest another man behind a barbed wire fence beckons and directs him to the entrance of a camp. Here the traveler encounters the inmates of the camp.

The visitor meets a gardener, who offers him a severed hand. He rejects this and moves on. He looks into the window of one of the buildings, and is invited in for dinner. Dinner consists of a butchered man, and the traveler is offered the victim's heart. He runs out and vomits, and is nearly drowned in his own effluence.

He emerges and encounters processions of inmates and victims. In one building a guard invites him to participate in the torture of other men. He refuses and runs out, encountering another guard, who directs him to the Palace of justice. After emerging from a maze, he is taken before a tribunal of three judges. For his refusal to participate in the affairs of the camp, the visitor is condemned to die, and is hanged. A parade passes the gallows, proclaiming justice, Freedom, Fatherland and God. The dead visitor is dragged to the crematorium and burned.

Out of the ashes a hand emerges. It is that of the visitor, and out of his scream a bird emerges. Clutching the bird as it flies from his throat, the visitor is flown out and beyond the camp. The traveler once again resumes his journey.

A Journey is at once a graphic masterpiece, stark, beautiful and moving in its simplicity, and a searing emotional experience, bringing forcefully to the viewer the pain, the frustration, the inhumanity of the concentration camp. It is the realization of a total Kafkaesque quality, rarely experienced in art. The viewer will become immersed in Lewen's world, a Kafka world of brutal bureaucracy, of dehumanization, of the total destruction of the human spirit. Unlike Kafka, however, Lewen in A joumey insists upon resurrection, survival and redemption.

A Journey

Si Lewen: A Journey (1 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (2 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (3 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (4 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (5 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (6 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (7 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (8 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (9 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (10 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (11 of 72)

Si Lewen:A Journey(12 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (13 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (14 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (15 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (16 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (17 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (18 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (19 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (20 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (21 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (22 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (23 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (24 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (25 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (26 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (27 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (28 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (29 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (30 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (31 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (32 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (33 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (34 of 72)

Si Lewen:A Journey(35 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (36 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (37 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (38 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (39 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (40 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (41 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (42 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (43 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (44 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (45 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (46 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (47 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (48 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (49 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (50 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (51 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (52 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (53 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (54 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (55 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (56 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (57 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (58 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (59 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (60 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (61 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (62 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (63 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (64 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (65 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (66 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (67 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (68 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (69 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (70 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (71 of 72)

Si Lewen: A Journey (72 of 72)